Comprehensive Guide to Lymph Node Removal for Breast Cancer

November 07, 2024

This article was reviewed by our Baystate Health team to ensure medical accuracy.

Holly S. Mason, MD

View Profile

Holly S. Mason, MD

View Profile

Health & Wellness Tips

Related Articles

-

Wellness & Prevention

![What are Different Types of Breast Cancer_ Plus Treatment Options]()

What are Different Types of Breast Cancer? Plus Treatment Options

-

Wellness & Prevention

![10 Breast Cancer Prevention Tips]()

Breast Cancer Prevention Myths and Facts from the Experts

-

Wellness & Prevention

![When to Get a Flu Shot]()

When to Get a Flu Shot This Year: What Experts Recommend

-

Wellness & Prevention

![a large lightning bolt striking from a dark sky during a severe thunderstorm]()

Storm Safety: Tips for Protecting Your Family and Home

-

Your Healthcare

![Woman pharmacist behind pharmacy counter, providing male patient with their medication.]()

Medication Safety: How Pharmacists Help You Manage Your Meds

-

Wellness & Prevention

![Over-the-Counter Birth Control Pills-What You Need to Know]()

Over-the-Counter Birth Control Pills: What You Need to Know

-

Coping with Illness

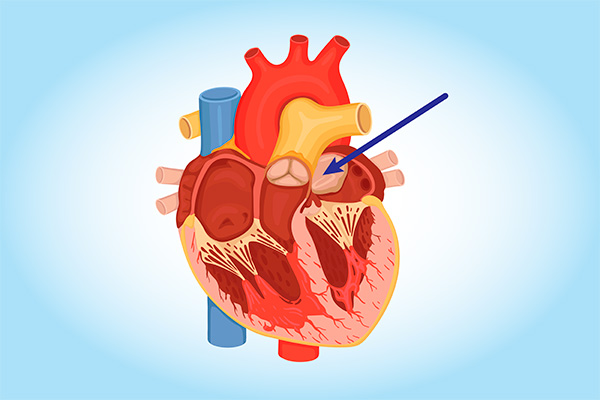

![cardiac myxoma heart tumor diagram]()

Can You Get Heart Cancer? It's Rare, but Yes. Learn the Symptoms

-

Wellness & Prevention

![Make your 2023 New Years Resolutions]()

5 Achievable 2024 Health-Related New Year's Resolutions

-

Wellness & Prevention

![feet in socks by a winter fire]()

Health Tips for the Holidays: Strategies to Stay Fit and Jolly

-

Wellness & Prevention

![a woman discussing pancreatic cysts with her doctor, waiting for an MRI scan]()

Are Pancreatic Cysts Dangerous? Do They Cause Pancreatic Cancer?

Back to Top